How to Make Soil

The U.S. is losing soil at an unsustainable rate. Rebuilding soil "up" takes a very long time. Luckily, rebuilding soil "down" is far quicker.

1. Headline

The United States is estimated to have lost roughly half of its productive soils over the past 100+ years, due to conventional farming practices that strip the land of important microbes and ongoing ground cover. If continued, it is believed that the country could exhaust its soil base in the next 80-100 years. Such news is often delivered alongside the very true reality that natural processes associated with rock weathering and plant/animal decay tend to build new soil supplies aboveground very slowly over long periods of time (e.g., 1,000 years). However, this does not mean that the U.S. and others like it face imminent peril. Regenerative agriculture practices like agroforestry can rebuild meaningful quantities of soil belowground in as little as one or two years, setting the stage for a hopeful rebound in this precious resource.

2. What does this mean?

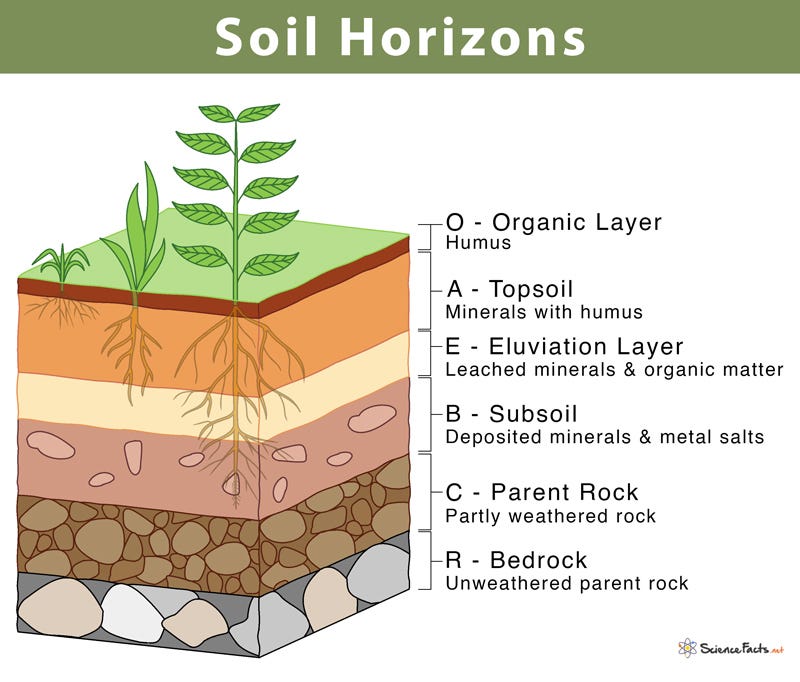

Soil is directly foundational to all human life on Earth, given its primary force as a medium for growing the food that we eat in order to survive. Without properly functioning soil, human beings wouldn’t last very long on this planet. It is therefore concerning that soils are under pressure globally, including in the United States. Productive American soils have been eroding by roughly 4.6 tons per acre per year for much of the 21st century, with ~40% of this displacement coming from water erosion and ~60% coming from wind erosion. Such levels of loss equate to roughly 1.9 mm (0.075 inches) of depth every year. To put this into further perspective, the lower boundary of U.S. soil is set arbitrarily at 2,000 mm, or roughly 78 inches. Within this horizon profile, the average A horizon (topsoil) height where most crops are cultivated in the U.S. is currently around 178 mm, or 6-8 inches.

Soil erosion rates in the U.S. have been steadily increasing over the past 100 years. It is now estimated that the country has effectively lost roughly half of its topsoil, with up to one-third of farms believed to have lost the entirety of their A horizons. Current rates of loss mean that the country would largely exhaust all of its productive soil resources within the next 80-100 years. This is a crisis on many levels. Politically, it is a national security concern as it relates to the ability of the nation to feed itself.

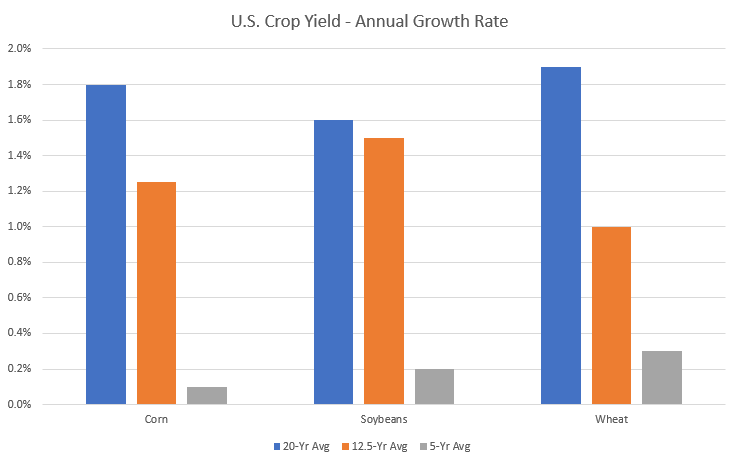

Although overall U.S. crop yields have been rising steadily for decades, yield growth rates on staple crops like corn, soybeans, and wheat have been slowing more recently (a new article in Nature doesn’t bode well for the country longer-term). As the chart below shows, U.S. corn yields have dropped from a 20-year average growth rate of 1.8% down to roughly flat over the past five years, according to USDA data. Soybean yields have dropped from a growth rate of 1.6% down to 0.2% during this time, while wheat yields have dropped from a growth rate of 1.9% down to 0.3%. Soil erosion represents an increasing headwind for farmers and society overall, as current displacement rates are measured to negatively impact crop yields by 0.4%, on average, per year. Some regions of the country face meaningfully higher yield impacts, relative to others.

What does all of this mean for the future of food production in the United States? Soil does regenerate naturally, on its own, however the process takes a long time. Soils are broadly composed of the grains of weathered rock and the remains of dead, decayed plants together with water and air. Thus, to rebuild soil “upwards,” human beings must wait on natural processes associated with rock weathering and plant/animal decomposition. Collectively, this process can take hundreds if not thousands of years. In fact, soils can only regenerate upwards by up to 0.5 tons per acre per year, or essentially 0.2 mm (0.008 inches) per year. Given such a long lead time - along with the ongoing threat of continued water and wind erosion - it simply isn’t practical to pin our hopes on natural soil regeneration above ground. At a minimum, we have to find a way to reduce soil erosion and protect what’s left in place. How do we do this?

Regenerative agriculture practices are a great start, given that they protect and enhance soils via methods that create soil organic matter (SOM). SOM is what binds soil together, made up of microbes like bacteria and fungi, mineral associated matter, and plant and animal tissues in various stages of decay (humus is the portion of organic matter that is fully decomposed, represented by a solid, dark-colored component that plays a significant role in controlling soil acidity, nutrient cycling, and hazardous compound detoxification). When higher levels of SOM are present, soils are considerably more productive…and resilient.

Historically, a good target for SOM levels in American soils has been 5% of the entire horizon profile. In fact, studies show that simply increasing organic matter from 1% to 3% can result in reduced erosion rates by an estimated 20%-33%, increasing water-holding capacity in the process. Reduced erosion (and disturbance more broadly) is incredibly important for soil, keeping decomposers like bacteria, fungi, and worms in place, helping to cycle carbon, nitrogen, and nutrients (these can get lost in erosion too) in a manner that produces more food for more people. This is a virtuous circle. Regenerative practices help to build organic matter within the soil, which in turn protects the soil from erosion, which in turn helps to feed more people.

The critical point to identify here is that SOM is, in effect, new soil and that regenerative agriculture itself is a way to spur new SOM development. Such regenerative practices create new soil “downwards” on a much quicker timeline relative to natural regeneration processes that build soil upwards. As a baseline of understanding, consider that plants take in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and eventually exchange organic carbon molecules via their root structures to organisms like bacteria and fungi in the soil for nitrogen, minerals, and other nutrients that help them grow. Regenerative agriculture practices help to restore and sustain this microbiology in the soil, enabling plants to facilitate greater levels of carbon sequestration underground. More carbon leads to more microbes which in turn leads to more SOM development getting pushed down throughout the soil horizon profile. Judith Schwartz captures this idea nicely in her book, “Cows Save the Planet.”

“This downward carbon flow stimulates the production of humus. The more carbon in the soil, the more energetic the microbes; the more energetic the microbes, the more mineral particles are broken down; the more minerals are broken down and made available to plants, the more humus.”

Mineral rock is not only located aboveground, but belowground as well. However, instead of a slow weathering process above the surface, the conversion to soil underground can be accelerated by the billions of microbes in place, if healthy conditions are allowed to flourish. When viewed through the vantage point of plant life, it is therefore not just the dead plant that ultimately gets converted to humus as it decays on top of the ground. The living plant (along with healthier soil management practices) can contribute to humus production, as well…downwards in the soil profile. Another excerpt from Judith Schwartz’s book…

“At depths below a foot soil does form - more rapidly than in the soil’s upper horizons…Here’s how: the…carbon compounds that are pumped down by the plant bolster the stores of organic matter. At the same time, the…carbon stokes the earth-dwelling microbes, which get to work dissolving the mineral portion of the soil. These minerals at once feed the plant…and build humus at a fast clip.”

How fast? The Winona story of Colin Seis and his family farm in Australia is one prominent example of how regenerative agriculture practices can quickly rebuild soil. After decades of conventional farming practices that severely degraded his land, Colin turned to regenerative pasture cropping (combination of crops and grazing animals) techniques alongside the removal of industrial farm chemicals. Over a ten-year period, the depth of topsoil on his farm more than quadrupled from four inches to eighteen inches (that’s 1.4 inches per year if you’re keeping score at home), in response. Similar results have been seen in the U.S., as well, like that of Adam Grady’s story in North Carolina and his ability to grow 3 inches of new topsoil in two years.

The science is relatively simple. Minimize soil disturbance and preserve webs of microbes underground; maintain living roots in the soil; keep farms covered year-round with living plants and crop residues; maximize plant diversity; reduce or eliminate chemical inputs; and integrate livestock, where possible. These regenerative agriculture principles will help to promote and rebuild healthier soils, improve water infiltration and quality, protect against erosion, sequester carbon, and produce healthier, more nutrient-dense food supplies.

Among the most common practices associated with regenerative agriculture (cover cropping, no-till, crop rotation, pasture cropping, green fertilizer), we believe that agroforestry is one of the best avenues for rebuilding soil. When commingled with crops and/or grazing animals, trees and their root structures help to drive all aforementioned regenerative agriculture principles, with research showing the following outcomes:

3. Key takeaway

The headline that the United States is losing soil at an unsustainable rate - and that this precious resource can only be rebuilt over millennia - is only partially correct. Although it takes upwards of 1,000 years to rebuild soil “upwards,” regenerative agriculture practices can add meaningful new quantities of soil “downwards” in as little as one or two years. At present rates of loss, wind and water erosion could lead to a full exhaustion of American soils in 80-100 years. However, if U.S. farmers and ranchers adopt regenerative practices like agroforestry, chances are good that the country will remain a safe and reliable supplier of food, as it works to stop soil loss and rebuild this critical resource over time.

4. Where to find us

Check us out on our homepage or come connect with us on LinkedIn.

We’re an investment fund that raises money from long-term investors to pay farmers and landowners to plant trees on their properties alongside crops and/or animals, returning nutrients to the soil and our food while delivering attractive, uncorrelated returns to investors.